- Home

- G. V. Anderson

Hearts in the Hard Ground Page 2

Hearts in the Hard Ground Read online

Page 2

There are some really personal things in here, she said. No one’s had the heart to shred any of it yet.

Flustered by my expression, she tried to explain: You said you were interested in the history — I waved it off with cries of no, it’s fine, it’s great! And once I got over the discomfort of going through a deceased woman’s stuff in her own home, I was genuinely moved by what I found. Shopping lists and housekeeping receipts; pocket-sized crossword puzzles; TV guides with certain programmes, presumably favourites, circled in blue biro; pamphlets from the local church; and postcards from Eastbourne.

The time flew by as we pointed things out to one another. Phrases that caught our attention, marginalia from a bygone era. When Mum passed, I missed out on this ritual — this meandering, sentimental sort-out. She’d settled her affairs and cleared everything out herself years ago while she still had a few marbles left, thinking to spare me the trouble. I appreciated the thought but would have welcomed trouble, when the time came; I’d have welcomed having something — anything — to do during the pre-funeral limbo other than needlessly cleaning our empty house. She’d lived there since her own childhood, and it was as bare as if she’d never lived at all.

Maybe that’s why I’d become so messy lately. The need to leave a mark. To take up space, unapologetically.

Thank you for this, I said, wiping my eyes. Really. And then, in a mad fit of daring, I took a deep breath and said, It’s five o’clock somewhere. Do you fancy a glass of wine?

* * *

The following morning found me with my bum on the coarse doormat and my feet out on the patio, tossing bits of mackerel to the tabby. He folded himself up and ate quietly, licking the stone clean and leaving dark little crescents behind. Hello, puss-puss, I called to him, rubbing my fingers like I had more food. He came forward and head-butted my ankle. Daft cat, I teased, scratching the base of his tail. Where do you live, then? In reply, he stepped right over the threshold, bold as you like.

The taxi had picked Annika up shortly before midnight. We’d finished the bottle between us, the drink loosening our tongues.

I knew now that she was twenty-seven and had started a BA in History and Anthropology at the university only to drop out when her immigration status became unclear. By the time her visa was reissued, her interest had soured. She barely knew what she wanted to do in life, working here and there in various administrative roles, covering maternity leave and so on. The estate agent had just given her notice, so she’d be adrift again next week. I don’t know if she was technically allowed to remove Claire Dockett’s papers from the premises, and I never asked. But if she was worried about the precariousness of her life, like I would be in her shoes, she masked it brilliantly. I told her about Mum and the little office job I’d taken. A three-month contract with the possibility of a permanent offer. She pushed for more, for my heartwood. What did you do before? Tell me about Fiona Parkman. What sort of person is she? Foggy with wine, I admitted that I … I actually studied nursing. Which was what led me to believe I could care for Mum.

So why didn’t I go back to that? Difficult to answer. I’d thought, I’d hoped, that all I’d need to be a good nurse was kindness. I didn’t know if I had any left. Let’s be honest, I hadn’t had much to start with. Sometimes I imagined my heart as a hard, brown pit; the sixpence you break your teeth on at Christmas, only not as lucky.

Did I say this aloud? Did I make an idiot of myself? Was I overly familiar after my third glass — a press of the knee, a teasing kick? Like the bruises on Mum’s arm, if I went over the scene again and again in my head, I could eventually trick myself into believing an alternate version. I could picture myself leading her upstairs to bed.

Suddenly, I heard yowling from the hallway. The tabby had pounced on Marley. (I was terrified all last night that Annika would hear him. So, she’d asked with her one-sided smirk, are there any ghosts here? I’d hardly known what to say.) I sprang up, knees cracking, and rushed over to separate them. Leave him alone, I snapped at the cat, shoo! And Marley, falling to pieces with each passing day, limped into the sitting room, trailing grave-dirt.

I watched him go, struck by how doddery he seemed all of a sudden. He’d lost his vim and, wrapped up with Annika, I’d hardly noticed it last night. Could dead things die? I hoped not. He’d been a constant presence from the day I moved in, a mud-hook in a shifting tide.

The hallway tiles felt chilly against my bare feet, cold and hard as packed snow. The wine had summoned no sleep last night. Charlie had been at it again, and the elongated hand, too, reaching and scraping and tearing for me. My bedroom door actually bulged inwards, yielding to some uncanny pressure; and out on the landing the boy’s cycle grew frenzied, the laughter short, the fall sure, as if his ghost was consciously flinging itself through the railing to escape whatever else lurked out there with him. I curled my toes and shivered at the thought of the impact.

* * *

That Sunday, I skipped the memorial garden and browsed the charity shops instead, looking for a rug. I brought a faded oval rose-patterned one home (along with a few daffodil bulbs for the garden) and placed it in the hallway. Luckily, I’m not one for looks because the colours clashed something awful. I visited the memorial garden the following week but by then the damage was done; the spell broken. Guilt dogged my heels for a while. It’s only a stone marker, I told myself. She can’t expect me to stare at it every week. She’d feel sorry for Charlie too, and do what she could to provide a cosier floor, a softer landing — or at least the illusion of one.

* * *

Claire Dockett had lived in my house since the early noughties. The stain in my bedroom marked where she’d lain, seeping, until the neighbours missed her, and was still livid as the day she died. Odd, then, that it took her so long to pay me a visit. I’d replaced the linoleum in the utility room; the garden had thawed. Her snowdrops had wilted, supplanted by my daffs, by the time she shuffled into the sitting room in late February.

She sat on the sofa with a groan, in a spot I’d never used and now never would. The tabby, curled up asleep on my feet, hissed. I poked him quiet with my toes. The Doors were playing on the turntable. Mum always hated them. Keeping my eye on Claire, I stretched out and lowered the volume.

Hello, I said.

She tilted her head, cataracts shining. I heard her mumble something. Mum had mumbled a lot, too. Like kindness, patience was never one of my virtues. Once, I lost my temper trying to make sense of her slurred speech. I never forgave myself for the things I spat in frustration. I recalled the memory now, with Claire, as a reminder to hold my tongue.

But Claire didn’t want conversation. She’d been alone much longer than I, and liked to haunt her home the same way in which she’d lived: unassumingly, with handicrafts and a cup of hot malt. Something placid playing on the radio. Not quite Jim Morrison perhaps, but we managed. I noticed her hands plucking at her shawl, pining for an occupation, so I gave her Mum’s knitting needles. God knows I hadn’t used them. She clacked away quite happily with those once or twice a week, at peace with her own mind. That was her lesson to impart, I think. How to sit back and enjoy life’s little comforts and indulgences. Warm pyjamas at the end of a long day. A square of chocolate after dinner. A completed puzzle. The gradual reclaiming of agency that builds to bigger things like lunch away from your desk, a solo day-trip, and searching for nearby nursing vacancies. Even the tabby graduated from my feet to my lap. I suppose you deserve a name if you’re planning to stick around, I muttered. When he kneaded my thighs with his pin-needle claws, I cried with relief at the pain.

I was moved most of all by the sense that Claire was giving me back the evenings I’d lost with Mum — the two of us together, alone. A second chance at making that elusive transition from mother-and-daughter to … I don’t know. Friends? Companions? A shot at knowing her as something besides a mother, anyway.

* * *

Hey, I said to Claire one weekend, these must be yours.

I’d found a few old Polaroids in her box of things. I liked to go through it occasionally, lying on my belly flipping through snaps, my new log-burner warming my feet; winter was reluctant to loosen its hold, that spring. She turned her head towards my voice. Here’s you on holiday, I said, flipping the photograph over. Someone had written the date on the back. 1974, Eastbourne, I said — Remember that? There had been a postcard too, I was sure … I rifled deeper until I found it. The front boasted a garish painting of the prom with white buildings on the right and sea on the left, and tourists eating ice cream at the railings. Every peep of skin was ivory; everyone wore bright block colours. On the flipside was a brisk salutation, a thank-you-for-coming-to-stay, an anecdote. Just enough to fill the space provided without sacrificing neatness.

Signed, Aunt Patricia.

If this postcard was referencing the same holiday in the Polaroids, that placed it seven years after Charlie’s death. I wagged the postcard, deep in thought. The dates made sense, the address was right — this must be the spinster Annika told me about, the one accused of murdering Charlie. So, a young Claire had kept in touch with her disgraced aunt, had she? I wondered what the Bryants had thought about that.

Do you miss her? I asked Claire gently. Patricia?

Claire never usually reacted to anything. This time, her nostrils flared. The clacking of needles stopped. The house darkened. Pressure, as if I was sinking into deep water.

From the corner of my eye, I saw a body hit the hallway rug.

It was only eight o’clock. Charlie never, ever fell before three. For the first time, I was close enough to hear his mewl of pain, like a half-crushed fox on the roadside, waiting to die.

I forced myself to stare ahead. Don’t turn; you don’t want to see a dead child; you can’t help him. Resentment rolled over me like thick, cloying fog. A shadow moved on the stairs. I heard a scraping of untrimmed fingernails along the wall. A drone like slowed-down static. The ghost from the landing, invoked by a name: Patricia. I glanced just long enough to see her coming — don’t look at the boy; don’t look at the halo of grey mush; don’t feel bad that the rug does nothing, a rug wasn’t there the first time — and when I turned back to the sofa, Claire was gone.

It angered me, sitting there, scared to move in my own house. Charlie and Claire were harmless. They were caught on a loop. In time, they would wear out like cassette tape. But this aunt, refusing to rest, to let go her grudge, scoring my door and floorboards and exacerbating a hundred lonely nights … My house of dead things might have been a home if not for her.

Patricia, I said through gritted teeth, you are not welcome here. Leave me alone.

Fiona?

I said leave me alone!

Fiona? Are you okay?

A metallic clatter. The letterbox! I jumped up to check the window. Annika was at the door. When she saw my face through the glass, her concern faded to relief. She held up a bottle of wine. Are you free?

I pulled the curtains shut and stormed through the hallway to let her in, sparing no attention for the boy or the shadow or the marks in the wallpaper. They’re not there; they don’t exist. Go away, Patricia, I muttered under my breath. Just go away.

When I threw open the door, Annika frowned at the look on my face.

Is it a bad time?

I inhaled the evening air. Petrol fumes; an idling engine. Gently frying oil from the chippy across the road. Car doors slamming; laughter. The chirp of a distant traffic light crossing. It was all so normal. I held my breath. My heart jerked. Nothing stirred behind me.

Fiona? I heard you shouting…

Clutching the front of my jumper, I told her I’d fallen asleep in the armchair — asleep at eight on a Saturday night! I had a nightmare so it serves me right, I said, laughing.

If you’re tired, I can come back another time.

No! I reached for her hand; could she feel my pulse racing? No, I’m awake now. A bit of company is just what I need. I didn’t tell her I was afraid to be alone. I’d felt such dark resentment before and had thought myself free of it, but now it simmered within reach and the only thing keeping it at bay was — Annika. Annika no longer waiting primly for me to pour the drinks, but following me into the kitchen and lounging against the counter, talking about her day. Annika showing me a picture of her new nephew on her phone. Annika rolling a joint with that sideways smile.

Can you believe it’s been almost five months since you moved in? I thought we should celebrate.

Jesus, Annika, I haven’t smoked since school.

Come on, old timer. She slapped my shoulder. I’ll show you how the kids do things nowadays.

Fuck you, I’m not that old.

The cat without a name watched as we got drunk, then mortifyingly high. Like, lead-weights-strapped-to-our-limbs high. We forgot our names and where our bodies ended. We didn’t make it to the bed.

* * *

At three in the morning, we were still tangled on the sitting room floor. Time for giggle, shriek, smash.

…

Fiona? What the fuck was that?

* * *

There comes a time when you have to confess what haunts you. You have to peel back the plaster and show your bare bones to someone — your copper piping and weight-bearing walls, the stains in your floorboards and the dead birds in your chimney — and you have to trust that they won’t scream. When Annika heard Charlie fall for the first time, when she crawled out from under me and saw him crumpled upon the rug, I knew I couldn’t hide my ghosts anymore. She nursed a black coffee while I went to the utility room to fetch what remained of Marley, my Marley; he lay twitching in his nest, the air fresheners brown and crisp with age twirling like cot mobiles, and she got a good look at him before he disintegrated in my hands. I sobbed as we reburied his ashes deep in the pliant spring soil.

Annika stayed to meet Claire that evening, and we were still smoking on the patio when Charlie fell again later that night. She was not squeamish. She went inside immediately to sit with him, wrapped in one of my sofa throws. I hesitated, not wanting to get too close — when Mum fell, I hadn’t been quick enough to catch her; every second she lay there, her wrist broken, must have been torture — but Annika pulled me down with her. She talked the ghost through his last terrified moments the way I’d coaxed Mum to her feet. I doubt Charlie heard her, his death having been set in stone a long, long time ago, but I loved her for trying.

She kissed him as he faded till tomorrow. With blood on her cheek, she asked me, Is that all? With a smile so pitying it hurt. These were nothing, I longed to tell her. Is that all? Oh, if only.

There’s one more, I said.

Who?

I shook my head. I couldn’t stomach it. Annika had seen enough tonight, more than enough. Patricia meant something too raw even for me.

They’re just ghosts, Fiona.

You don’t understand…

Cast them out. This is your house now.

* * *

Monday dawned, bringing real life with it. Annika left for work: an eight-hour shift in the Natural History Museum café. I didn’t ask her to call in sick to stay with me. She loved that job, though it killed her feet, and as good as she’d been with Marley, Claire and Charlie, she must have been glad to disappear for a while into a world where the biggest concern was whether they had enough clean cups. My permanent offer from the office had never materialised so I had nowhere to be; I watched her go from the doorstep, and when the beat of her loafers on the pavement faded, I turned to look up the dark, shifting stairs.

Did you hear that? This is my house.

The darkness that was Patricia, impervious to the sunlight streaming in through the front door, slyly retreated. I watched her slink all the way up into the loft hatch. So that’s where she’d rooted herself like a snail, her shell’s nub: at the highest point of the house. I brushed my brow, tucking my hair behind my ear. I had to face her, or this place would never be mine.

I grasped the bannister and haule

d myself up, fighting the pressure pushing me down. Static blocked my ears, my skin fizzled. The stairs grew feverishly hot underfoot. Finally, I stood beneath the hatch. There was a cord to pull on, but the ladder was rusted and refused to extend. I cleared my vanity — chucking the mirror on my bed and disturbing the cat; Sorry, Puss — and dragged it onto the landing. It took my weight, just, though I had to brace one foot upon the railing in order to pull the ladder down. It was a rickety thing, that railing. A cheap replacement for the one Charlie fell through over fifty years ago. It didn’t take much to imagine it breaking, or for my sweaty sole to slip … I’d install another, I promised the house as I climbed the ladder. I’d install a hardwood railing, strong as bone.

I’d never been in the loft before. When you have barely enough stuff to fill the rooms you use day to day, there’s no need for one. Mine had a proper floor and a grubby dormer window overlooking the back. Annika had warned me about the junk left up here, boxes and furniture the estate agent hadn’t bothered to clear, but I hadn’t expected to see a bedframe and nightstand. This was a garret. Houses like mine had employed maids once, and this was where they must have slept. This was where Patricia had slept, hidden out of the way as if she were staff, not family.

She slid alongside me suddenly, a gelid creature. I grabbed a beam to steady myself. The wood was worn smooth as skin.

How can you be here? I asked. You left.

Deaths, she told me, aren’t the only things that accumulate in old houses. Did you never question why the boy replays his end yet the crone does not? Quiet moments impress themselves upon a house as well as hideous ones. So do years passed in solitude, years in which you’re expected to come running like a dog when the bell chimes. You survive on the goodwill of family who resent having to keep you, and the charge you’re told you’re meant to love often spits in your face, calls you names.

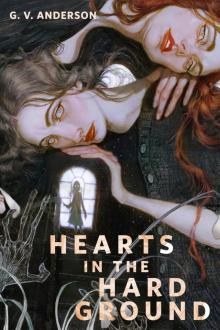

Hearts in the Hard Ground

Hearts in the Hard Ground